Faces of Water: The conquest of water

In the face of political division, the women of the Pedregal of Santo Domingo organized their neighbors around the issue of water access. Their efforts won the neighborhood a well that guarantees the supply of water in their homes.

Doña Fili's presence is not as ubiquitous as it used to be at protests of autonomous movements in Mexico City –because she is now “about a hundred years old,” she jokes– but taking her place is her daughter, María Elena López. Male, as she is affectionately called, is a woman of sweet and firm words, with abundant straight hair that she usually pulls back to reveal her watermelon-shaped earrings. She crocheted them herself in solidarity with the Palestinian people in the face of the ferocious genocide that began in October 2023. Needle and thread have become a form of political struggle for Male and other women from the neighborhood, with whom she founded the Yaocihuatl Pedregales collective.

During the Aztecas camp, the neighbors received a visit from the mothers and fathers of the 43 missing students from Ayotzinapa, victims of forced disappearance whose whereabouts are still unknown after a decade. They decided to embroider the portraits of the young people on napkins, which years later have traveled the world and even visited Montevideo. Yaocihuatl means “warrior woman” in Nahuatl, and their embroideries were part of the exhibition Giro gráfico, como en el muro la hiedra, dedicated to social protest across the continent.

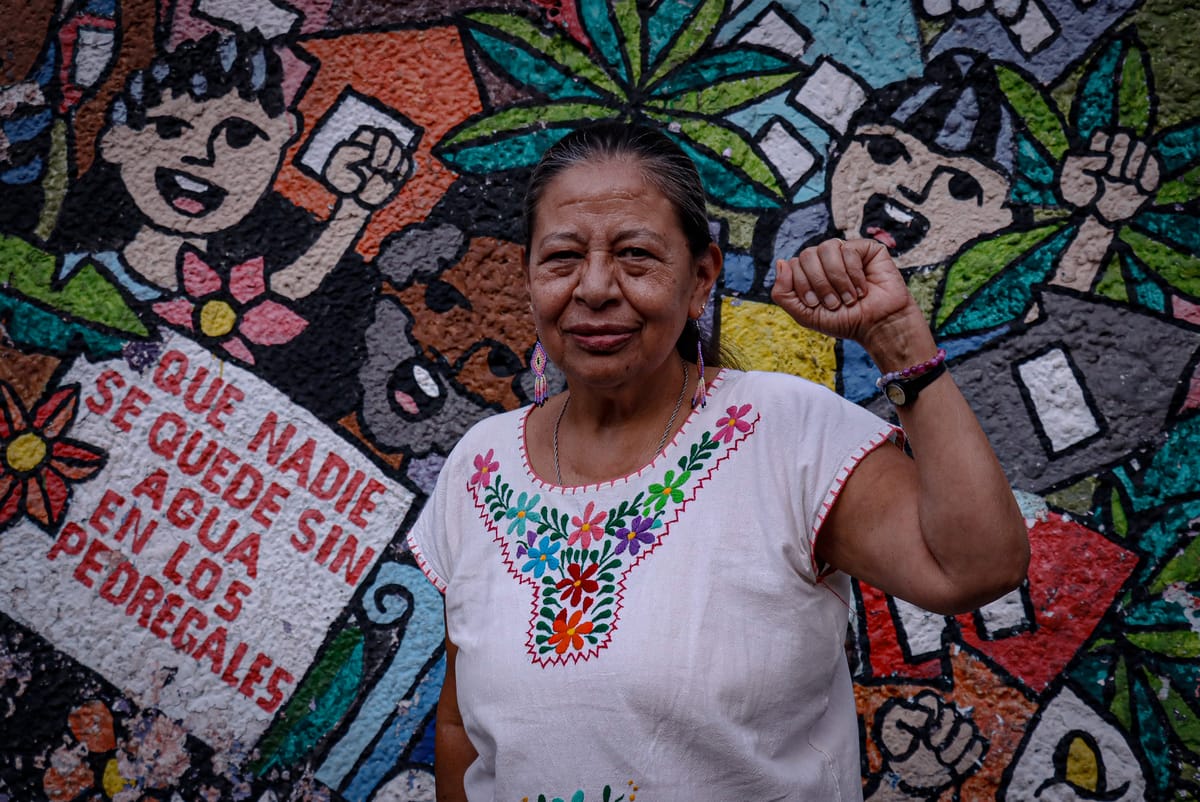

The Yaocihuatl collective is not the only daughter of the Aztecas 215 sit-in. By the end of 2021, the Committee in Defense of Water succeeded in getting a new well built to supply the Pedregal de Santo Domingo neighborhood. Born out of the Aztecas struggle, the Committee has continued a local tradition, as María del Carmen Pelayo, a long-time neighbor of the neighborhood and member of the Committee, recalls.

“The neighborhood was founded 52 years ago, and we have been suffering from water for 52 years, because the authorities have always used it as political booty. They give it to us in drips because it is a way of pressuring people to vote for them. We do not agree with these bad practices, and that is why we started a movement,” she says.

And it was a tough fight, house by house: “We started to fight with the authorities. They said no and we said yes.”

To demonstrate and unify the common will, they gathered more than a thousand signatures from neighbors demanding the construction of the well, one of the first to be built in the Mexican capital by popular demand.

“We had many problems with neighbors and people who knew they were going to run out of political spoils. In the beginning, there were 'leaders' in the neighborhood [who functioned as the parties' contact with the base] who pulled people to their side. If one was a leader of three blocks, he would fight for those three, while another one from further away would fight for his own and the others for theirs. What we are trying to do is to get the people of the neighborhood to unite, regardless of their economic position, where they live or how many people live at home. We want to have a sense of community,” says María del Carmen.

Once the well in Santo Domingo began to operate, the supply began to fail. In March 2024, the Committee warned the authorities that they would occupy he well if the issue was not resolved soon. It worked. By forced marches and under permanent surveillance, they guarantee access

“We are a little school of struggle,” says Male. She relates how other neighbors in a nearby neighborhood, in downtown Coyoacán, have sought the Committee's guidance to replicate their experience in receiving their own well.“It’s not a working class neighborhood, but it is amazing how with real social struggle, progress is made. Even though they asked for the well, they haven’t gotten it, so they came to us and asked.” They also frequently meet with professors and researchers from Ciudad Universitaria, UNAM's main campus in the capital, who are interested in the local process.

“That has allowed us to get to know other struggles and not become stagnant, because whenever we are invited, we go. It's nice to know that there are other territories standing up, who we can walk alongside, even if we only know them by hearsay,” says Male.

Water management and scarcity became a central issue in the 2024 campaigns to govern Mexico City. Among the candidates' proposals was the creation of a social water comptroller, but beyond the politicians' speeches, the Pedregal neighbors are a living example: they built, in practice, a form of community water management.

It is paradoxical how in this struggle the majority are women.“I feel that we are more combative and insistent about things,” says María del Carmen. María Santiago explains it in greater depth: “We say that women are always ahead, that if a woman advances, there is no man who can stop her. We women are the toughest. The most hard-working, the most chingonas, are always the women. The man goes to work, but it is the woman who carries the heaviest burden: she has to take the time to cook, to care for the children, to see that they go to school, to take care of the chores. If I don't have water, I am not going to wait until my husband arrives to fetch water. We as women see the need we have in our homes.”

Text: Flor Pagola, Caro Bas, Madeleine Wattenbarger and Eliana Gilet

Photo: Lizbeth Hernández

Design: Paola Macedo

This story is part of Faces of Water: Stories of Women Defending Water in Montevideo and Mexico City, a project by the Cooperativa de Periodismo and Kaja Negra, supported by the 2024 ColaborAccíon grant from the Fundación Gabo and Fundación Avina.